Pietro da Cortona

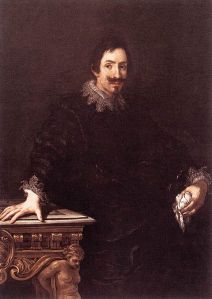

Pietro da Cortona, Portrait of Marcello Sacchetti, ca. 1626, High Baroque, patron: Marcello Sacchetti, oil on canvas, 52″ x 39,” Galleria Borghese, Rome

Pietro da Cortona’s (1596-1669) Portrait of Marcello Sacchetti illustrates Cortona’s relationship with patrons and his study of antiquity. The Sacchetti family were wealthy Florentines who moved to Rome, marked by Marchese Marcello Sacchetti who was Urban VIII’s treasurer beginning in 1623 (Harris, 14). Most of Cortona’s work during the 1620s was commissioned by the family (Harris, 14). With the patronage of the Sacchetti family early in his career, Cortona was also introduced to other aristocrats with humanist and antiquarian interests, such as the Mattei family. The Sacchetti’s patronage from 1623-1624 established Cortona’s career, since the family was connected to the new reign of Urban VIII and Barberini circles. Cortona also built the Villa Sacchetti for the family at Castelfusano, 1625-1629, his first architectural project (GOA). The Villa was modeled on Renaissance buildings and the classical tradition, but heightened to the spectacle of the Baroque with the inclusion of giant staircases, a spectacle connotation, a performance of architecture and art. The Villa exemplifies the High Baroque elements emerging, with a dynamic classical approach. Cortona worked in multiple mediums, like Bernini and Raphael, continuing the Renaissance ideas of what gave an artist authority with the understanding of disegno. The portrait of Marcello Sacchetti depicts him with a limited number of objects, but specifically chosen pieces to illustrate his attachment to the study of antiquities with the detail of the table, which Cortona also studied beginning in the early 1620s with Cassiano dal Pozzo (GOA). The minimal indications, such as the handkerchief to represent the wealth associated with lace, gives a stature to the portrait of his patron. Cortona’s portrait demonstrates the importance of patronage for the rise of his career.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

Merz, Jörg Martin. “Cortona, Pietro da.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T019663. 26 March, 2013.

Pietro da Cortona, Martyrdom of St. Martina, n.d., High Baroque, patron: Cardinal Francesco Barberini, oil on canvas, location not found

Cortona’s Martyrdom of St. Martina represents the shift to the High Baroque style of dynamism and movement in altarpieces. In 1634, Cortona began the rebuilding of SS. Luca e Martina, the church of the Accademia di S. Luca in Rome (GOA). Similar to his contemporaries, Cortona’s work on the church illustrated the multiple mediums mastered by High Baroque artists to create an interdisciplinary work. S. Martina was uncovered in 1634, including a ceremony, which reflected the importance of uncovering new saints during the strengthening of principles and programs of the Catholic Church. The rebuilding of SS. Luca e Martina also included the patronage of one of Urban VIII’s nephews, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, one of the sponsors for rebuilding the church and a patron for Cortona, as he was transitioning from living with the Sacchetti family. Cortona also became responsible for the altarpiece for the decorative program, displaying an example of High Baroque altarpiece as the work moves from the Early Baroque Carracci format, but still retains an asymmetrical composition, with the architecture on one side anchoring the work, while the view moves into the background. Cortona’s figures in the altarpiece become characterized by diagonals, no longer stable, but have a dynamic quality, as if spinning. The hourglass shape of the composition continues the dynamic forms and asymmetrical composition, with St. Martina as the bottom of the glass form, and the putti becomes the upper part. The spiral element becomes enhanced by the drapery and the clouds, while retaining the classical tradition of the frieze across the foreground. Cortona studied the work of Titian, who completed similar compositional format with the use of putti and clouds, emphasizing the heavenly and earthly hierarchy. The use of architecture defines the distance and space of the composition, as the different steps to go into the distance, a development seen previously with extreme distance emphasized by the inclusion of figures and architecture. His work during the 1630s becomes characterized by warm, sensuous, and richly colored forms, as seen with St. Martina, since Cortona believe painting should unite the disegno of Raphael and Titian’s colore (GOA). Cortona plays with the classical forms, but includes active and dynamic elements of movement, becoming an influential figure in the High Baroque.

Merz, Jörg Martin. “Cortona, Pietro da.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T019663. 26 March, 2013.

Pietro da Cortona, Process of St. Charles Borromeo during the Plague in Milan, 1667, High Baroque, oil on canvas, S. Carlo ai Catinari, Rome

Cortona’s Process of St. Charles Borromeo during the Plague of Milan illustrates the continuing use of diagonals to enhance classical traditions, while reflecting the importance of new saints emerging. The scene depicts the newly created Counter-Reformation saint, Charles Borromeo during the event that characterized his saintly behavior of going out into the streets of Milan among people during a plague of the 1570s. Cortona uses similar compositional strategies of distance, emphasizing the importance of foreground with the main figures and the strong diagonal enhanced by glimpses of architecture. Cortona employs a shift in scale from the foreground to distance through the use of the canopy’s diagonal. The figures in the foreground also continue the tradition of mirroring each other to create an entry and exit into the picture, keeping the viewer in the act of reading the work, part of the classical frieze tradition. Cortona continues the use of diagonals to create a dynamic composition, as seen with the diagonal from the plague victim to Charles, then to the angel, reinforced by the canopy and dramatic light. The torches carried by the figures also provide strong diagonals, displaying Cortona’s skill in handling light and representing the flicking of light due to wind, mirroring the light that would have been the church environment of the painting. Cortona’s ability to create a pattern of color unifies the composition, enhanced by the pattern of light and dark, which involves a theoretical concern for compositional unity from the classical approach. The observation of Venetian artists later in Cortona’s career integrates a more painterly approach, as the texture of the brushstrokes also unifies the composition. Cortona’s work represents the High Baroque use of diagonals and unification of composition through color.

Merz, Jörg Martin. “Cortona, Pietro da.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T019663. 26 March, 2013.

Pietro da Cortona, Rape of the Sabines, 1631, High Baroque, patron: Marcello Sacchetti, oil on canvas, 9′ x 13′ 9,” Pinacoteca Capitolina, Rome

Cortona’s Rape of the Sabines represents the dynamic classicism emerging with Cortona’s High Baroque style. The work depicts the historical event of the rape of the Sabine women, but was accompanied by several other works for the Sacchetti family to decorate their Roman palazzo, Palazzo Sforza Cesarini (GOA). The mythological series, such as Triumph of Bacchus, referenced masterpieces in several palaces and villas around Rome, but Cortona emphasized his representations as the newest adaptations of these subjects. The work was a complement to the other mythological subjects, connected to the wedding of Giovanni Francesco Sacchetti and Beatrice Tassoni Estense (GOA). The series was meant to be compared to Annibale Carracci and Raphael, while illustrating Cortona’s ideas about narrative and painting. Cortona creates an illustration of dynamic classicism, with the classical frieze composition, but the main figures move left to right to represent a dynamism, also with the groupings in the use of diagonals. The subsidiary compositional forms lead to an increased movement in the work. The architecture on either side creates a distance in the space, while Cortona creates a stage-like setting for the foreground. The architecture employs classical elements for a story of antiquity, referencing his knowledge of antiquities and his patron’s interest. With the dramatic treatment in subject, Cortona also unified the composition for a unity of narrative through the painterly brushstrokes, blending one form into another. The patches of color distributed through the composition also unify the movement of each figure. Cortona uses different facial expressions, a stage-like effect. He continues the use of the spiraling energy of the diagonal to heighten the dramatic in his work. Cortona establishes a new approach to classical narrative, or historia, by emphasizing scenographic, stage-like dramatic action scenes through the use of gesture and affetti with arrangement of figures. Cortona with the pictorial surface wanted to establish painting’s superiority to sculpture (Harris, 114-115).

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

Merz, Jörg Martin. “Cortona, Pietro da.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T019663. 26 March, 2013.

Pietro da Cortona, Glorification of the Reign of Urban VIII, 1633-1639, High Baroque, patron: Cardinal Francesco Barberini, fresco, Palazzo Barberini, Rome

Cortona’s Glorification of the Reign of Urban VIII (or, Allegory of Divine Providence) utilizes illusionism for a new treatment of ceiling decoration. Cortona had previously used quadri riportati for ceiling decoration, but with the fresco ceiling of the Salone in Palazzo Barberini, Cortona used a combination of painted architecture and sculpture, overlapping narrative to create a unity (Harris, 119). Cortona employs illusionistic architectural framework in the decoration of the vault, leading to a unified surface (GOA). Cortona created a feigned architectural framework, with four mythological subjects along the central field (Martin, 164). The decoration depicts historical and allegorical scenes to represent the virtues of the Barberini, specifically the triumphs of Urban VIII, and his immortality (GOA). The representation of allegory of divine providence becomes connected to the reign of Urban VIII, consisting of five main units (Harris, 119). The upper part of the central rectangular area illustrates a large laurel wreath held by theological virtues, while above them, Rome holds the papal tiara and Religion with the crossed keys of the papacy (Harris, 119). Cortona integrates three golden bees, the Barberini symbol. The viewer looks up into space, as the allegorical women are overhead (Harris, 119). The smaller figure of Divine Providence creates a triangle comprising of Saturn and the Three Fates, as their cloud banks overlap the ornamented stone entablature, and piers support the four corners of the ceiling (Harris, 119). Cortona creates a division of two sections, emphasized by the allegorical women moving into the central area from the sides (Harris, 119). Cortona also depicts an airy space through the use of light and color (Martin, 164). Cortona characterizes the High Baroque as an art of rhetoric, as the artist adopts a new triumphal attitude for the Church.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

Martin, John Rupert. Baroque. New York: Harper & Row. 1977.

Merz, Jörg Martin. “Cortona, Pietro da.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T019663. 26 March, 2013.

Pietro da Cortona, Trinity in Glory, Assumption of the Virgin, 1647-1651, High Baroque, fresco, S.M. in Vallicella, Chiesa Nuova, Rome

Cortona’s Trinity in Glory and Assumption of the Virgin illustrates the High Baroque’s characteristic illusionistic treatment. Cortona worked on the fresco decoration of S.M. in Vallicella, completing the half-dome apse of Assumption and the cupola of Trinity (Martin, 164). After his return from Florence, Cortona worked in Chiesa Nuova (GOA). The two scenes are separated into separate architectural fields, but Cortona involves the viewer in the space through the illusionistic treatment of the scenes. The viewer in the nave, sees the two scenes, as unified, since Cortona connects images across “intervening space” (Martin, 164). Mary is on clouds within the lower zone of the space from the vaulting of the apse, but Cortona’s illusionistic treatment creates the appearance of Mary ascending toward the cupola to Christ and God the Father (Martin, 164). The crossing of spaces represents the ascent into the celestial realm of the dome (Martin, 164). Cortona ultimately involves the viewer, since the ascent occurs in the viewer’s own space within the church, bridging the space between earthly and heavenly realms (Martin, 164).

Martin, John Rupert. Baroque. New York: Harper & Row. 1977.

Merz, Jörg Martin. “Cortona, Pietro da.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T019663. 26 March, 2013.

Andrea Sacchi

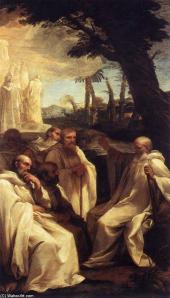

Andrea Sacchi, Vision of St. Romualdo, 1631, High Baroque, patron: Cardinal Lelio Biscia, oil on canvas, Pin. Vaticana, Rome

Andrea Sacchi’s (1559-1661) Vision of St. Romualdo represents the contrast in High Baroque styles, exemplified by the reduced manner of Sacchi and the dramatic movement of Cortona. Sacchi’s work was commissioned for the high altar of the Camaldolese Order in the new church in Rome, S. Romualdo (GOA). The scene depicts a group of Camaldolese monks listening to the saint retell his vision, as the vision is depicted behind them (GOA). Sacchi characterizes each monk with individual attributes, an element Sacchi continues in his work to focus upon a select group of figures (GOA). Sacchi exerts a control on the color and tone, blending Baroque and Classical art, compared to the dramatic movements and painterly approach of Cortona (GOA). Sacchi saw the purpose of art as representing serious morals, instead of being purely decorative (GOA). Sacchi’s work represents the reduction to the essential elements of the scene to illustrate the morals of the saint. Sacchi debated with Cortona at the Accademia di S. Luca in 1636 concerning the virtues of compositions containing few or many figures (GOA). Sacchi symbolizes the subtly and reduced side of the High Baroque.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. “Sacchi, Andrea.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T074853. 26 March, 2013.

Andrea Sacchi, Divine Wisdom, 1629-1630, High Baroque, patron: Cardinal Antonio Barberini, fresco, Palazzo Barberini, Rome

Sacchi’s Divine Wisdom continues his use of few figures and reduced composition to represent a moral virtue. The ceiling decoration, part of the Palazzo Barberini’s, was in the antechamber to the private chapel of the family (GOA). The decoration depicts Divine Wisdom and the different qualities, illustrated by the eleven seated women, such as Nobility and Justice (GOA). The allegorical women’s attributes also correspond to a constellation, with some stars (Harris, 121). The allegorical representation does not involve the framing of quadratura architecture, but involves seen from below, the illusion that the ceiling of the room is an open sky (GOA). sirens along each corner holding Barberini suns, while bees, the family symbol, are integrate on the throne and framing frieze (Harris, 121). Sacchi references an apocryphal text in the Barberini archives, in which Divine Wisdom rules the world with the help of divine archers, represented by the winged youths, who move us toward love of wisdom or fear of its absence (Harris, 121). Sacchi individualizes each of the women, referencing the importance he placed upon fewer figures to focus upon individuality. The classical ceiling decoration is above the chapel, reminding the viewer to pray for guidance from Divine Wisdom (Harris, 122). The globe in the scene also references Sacchi’s awareness of contemporary scientific thoughts, such as Galileo’s heliocentric theories, due to his first patron, Cardinal del Monte. The subtle colors and reduced composition represent Sacchi’s characteristic of focusing on a work based on morals and virtues.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. “Sacchi, Andrea.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T074853. 26 March, 2013.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.