Seville

Francisco de Zurbarán, Battle of the Christians and the Moors at El Sotillo, 1638-1640, Spanish High Baroque, patron: Carthusian monastery of Santa Marĺa de la Defensión at Jerez de la Frontera, oil on canvas, 11′ 1″ x 6′ 3 1/4,” Metropolitan Museum of Art

Zurbarán’s Battle of the Christians and the Moors at El Sotillo reflects the Baroque element of depicting time in a visual form. During the 1620s and 1630s, Zurbarán became involved with monastic patrons in Seville, receiving a commission for an altarpiece for the Carthusian monastery of Santa Marĺa de la Defensión at Jerez de la Frontera (Tomlinson, 71). Zurbarán depicts the Battle of El Sotillo, between the Christians and Moors, with historical accounts including the Virgin enthroned against the heavens, revealing to the Christians, the Moors who are ready to ambush, but are ultimately defeated (Tomlinson, 72). The work illustrates secular and religious histories united, referencing the importance of religion in the Spanish Baroque environment (Tomlinson, 72). The scene represents the triumph of Christianity and the involvement of divine intervention, as the Christians become the chosen people (Tomlinson, 72). With the combination of secular and religious histories, Zurbarán also represents both past and present (Tomlinson, 73). In the foreground, a pikeman is dressed in contemporary costume, serving as an intercessor as he directs attention to the Moors in the middle distance (Tomlinson, 73). Zurbarán includes multiple centuries from foreground to middle ground, involving the spheres of the past and present, delineated by the costumes and lighting (Tomlinson, 73). Zurbarán utilizes Baroque elements of time and the representation of the divine to reflect the importance of Christianity in the Spanish Baroque environment.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

Diego Velázquez, Old Woman Cooking Eggs, 1618, Spanish High Baroque, oil on canvas, 39 1/2″ x 46 5/8,” National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

Velázquez’s Old Woman Cooking Eggs illustrates the Seville trend toward naturalism during his early career. The naturalism of the work aligns with the Spanish Baroque style of naturalism, with the combination of still life and genre painting. Velázquez characteristically focuses upon the detail of the objects, combining still life elements with an activity. Velázquez was beginning to use the tenebrist naturalism of Caravaggio, seen in his bodegones, working with still life and daily life elements (GOA). Many of his scenes which combine still life and genre leave the question of a deeper meaning. Each object is individually depicted, highlighted in a dramatic fashion to capture the sensation of surfaces, while communicating his ability to represent diverse textures and surfaces. Each object represents a different texture and sheen, illustrating the skill in reflecting light. Velázquez involves a splayed perspective, influenced by Flemish art, with the figures in somewhat profile, while there is a view on top of the surface of the table, allowing the viewer to clearly see the elements of the scene, such as the bowl of eggs. Velázquez employs the play of perspectives, instead of a correct viewpoint to illustrate the diverse elements of the scene and reinforcing the observation of reality. The separating eggs continue the observation of nature and Velázquez’s ability to represent the material world. Velázquez mixes a Caravaggio style treatment of observation and Bolognese naturalism with Flemish genre painting, in the pursuit of creating an illusion of reality, a continuation of a Baroque theme.

Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. “Velázquez, Diego.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T088463. 23 April, 2013.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

Madrid

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Philip IV, c. 1625-1628, Spanish High Baroque, patron: Philip IV, oil on canvas, 6′ 5 1/4″ x 3′ 4 1/4,” Museo del Prado, Madrid

Velázquez’s Portrait of Philip IV represents the developing shift from the previous formal court portraits, to an individual treatment of the monarch. In 1623, Velázquez was called to Madrid to paint a portrait of the king, leading to his appointment as Pintor del Rey, becoming court painter and courtier (GOA). Philip IV Hapsburg (r. 1621-1665) continued the centrality of Madrid as the location of the royal court, serving as the chief patron. Velázquez was appointed through the influence of one of the king’s main advisors and patron, Count-Duke of Olivares. Velázquez painted several portraits of Philip during this period, illustrating his ability to represent individuals and the concept of monarchy, as the success of his portraits led to Velázquez becoming one of central painters to the king. The king is depicted in the manner he would have been seen by visitors, with the hat on the table behind him after greetings (Tomlinson, 87). The king stands next to the console table, referencing the etiquette of the Spanish Habsburg court (Tomlinson, 87). Velázquez focuses upon the illusion of reality and the observation of details, such as the stiff collar, or golilla (Tomlinson, 87). With the reworking of the portrait in 1628, Velázquez developed the details of black with the king’s costume (Tomlinson, 87). The use of chiaroscuro leads to a “hyperreality” with the depiction of the monarch (Tomlinson, 88). The limited palette and heightened contrasts develops a focus upon the individual treatment of the court portrait (Tomlinson, 88). The illumination on the hands and face continue the focus upon the individual features of the king. The standing portrait was rare and reserved for the monarchy, filling the entire space. The attire also represents the elegance of court costume throughout Europe, with the use of black garments and small hands and feet. Velázquez plays with perspective again with the view of looking straight on, but seeing the top of the king’s feet. The naturalistic details and simplified settings, accompanied with the domination of the figure, emphasize the individuality of the king’s portrait.

Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. “Velázquez, Diego.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T088463. 23 April, 2013.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

Diego Velázquez, The Forge of Vulcan, 1630, Spanish High Baroque, oil on canvas, 7′ 3 1/2″ x 9′ 6 1/4,” Museo del Prado, Madrid

Velázquez ‘s The Forge of Vulcan demonstrates the Spanish Baroque treatment of mythological subject matter. Velázquez created the work after studying in Italy in 1629-1631, in which his colors become more luminous with loose and vibrant brushstrokes (GOA). He studied the Roman Bolognese classicism, and the academic treatment of the nude and space, elements reflected in the work (GOA). Many subjects in Spain focused upon history and genre, but less mythology or allegory works, which were imported Flemish and Italian works. In Velázquez’s previous work, there was a sense of timelessness with the figures in their pose and early bodegones (Tomlinson, 91). With the scene depicting Apollo telling Vulcan the infidelity of his wife, there is an emphasis upon a psychological moment, reflected in the expressions of Vulcan and his workshop assistants (Tomlinson, 91). Velázquez’s figures are semi-nude, no longer in heavy draperies of his earlier paintings, but in graceful poses in a clearly defined illusionistic space (Tomlinson, 91-92). The bodies reflect Velázquez studying Greek and Roman sculptures, along with the Renaissance masters in Italy, but maintaining the naturalistic heads of Caravaggio (Harris and Zucker). The work incorporates warmer tones and a more painterly handling of the flesh, a style emerging after his return to Madrid in 1631 (Tomlinson, 92). Velázquez’s work reflects the moment of drama, a Baroque element, treated in a Spanish style with the direct influences of Italian contemporaries.

Harris, Beth, and Steven Zucker. “Velazquez’s Vulcan’s Forge.” Smarthistory. KhanAcademy. http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/velazquez-vulcans-forge.html. 30 April 2013.

Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. “Velázquez, Diego.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T088463. 23 April, 2013.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

Diego Velázquez, Rokeby Venus, 1648, Spanish High Baroque, patron: possible private commission, oil on canvas, 48 1/4″ x 69 3/4,” National Gallery, London

Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus illustrates his shift in style, while playing with the Baroque element of perspective. By the early 1640s, Velázquez was working in the royal household (Tomlinson, 98-99). After studying Titian in the royal collection, Velázquez depicts a similar subject matter of a reclining Venus, but through a personal treatment instead of the sensuality of Titian (GOA). The technique incorporates Velázquez’s clear strokes of color, or borrones, used to define the form (Tomlinson, 97). The modeling of the nude’s flesh becomes set off by the drapery behind (Tomlinson, 100). Velázquez involves a play of perspective with the reflection of the Venus and her position creating a separation of the beauty from the viewer (Tomlinson, 100). Though the viewer is able to see the reflection of the face, he is still unable to see her intimate parts (Tomlinson, 100). The provocative viewpoint contrasts with the religious and moral scenes of Spanish painting (Harris, 235). Velázquez depicts a mythological scene, while contrasting with the religious emphasis of Spanish Baroque painting with his involvement of perspective to create a seductive scene.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. “Velázquez, Diego.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T088463. 23 April, 2013.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

Seville

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, c. 1678, Spanish High Baroque, oil on canvas, 68″ x 112,” Museo del Prado, Madrid

Murillo’s Virgin of the Immaculate Conception reflects the Spanish Baroque focus upon religious pursuit and the atmospheric quality of Spanish artists. Murillo represented realism with a characteristic sentimental beauty (GOA). During his career, he illustrated various representations of the Immaculate Conception (GOA). Murillo’s Madonna figures demonstrate spiritual purity with idealized beauty (Tomlinson, 75). He involves the Baroque element of space, as the Virgin figure in heaven becomes defined by innocence and grace (Martin, 156). With the representation of the heaven and a divine presence, Murillo creates the work with an eternity with time and space, timeless (Martin, 156). The lighter tones and atmospheric paint creates an ethereal vision instead of reality, as artists after 1660 in Seville and Madrid illustrated visions of heaven in a new style (Tomlinson, 75). The iconography of the Inmaculada, from the Revelation of St. John, was familiar in seventeenth-century Spain, a belief that the Mother of God had been born without sin, emphasized by the sweetness represented by Murillo (Tomlinson, 75). The subject matter of the Immaculate Conception was being discussed in Counter-Reformation Spain, as Murillo’s work responds to the religious environment (GOA). Murillo’s representation involves Baroque qualities of space consideration, while shifting to an atmospheric effect with new styles emerging.

Martin, John Rupert. Baroque. New York: Harper & Row. 1977.

Mena Marqués, Manuela B. “Murillo, Bartolomé Esteban.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T060472. 23 April, 2013.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

Late Baroque Madrid

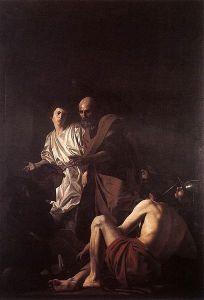

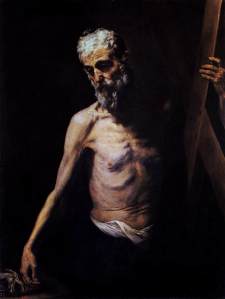

Luca Giordano, St. Sebastian Cared for by St. Irene, c. 1665, High Baroque, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Luca Giordano’s (1634-1705) St. Sebastian Cared for by St. Irene represents the Baroque expressive element of light, applied to a religious scene to involve the viewer in an the emotive quality. The work depicts the religious scene of Sebastian under the care of Saint Irene, while being a saint that is associated with surviving the plague, a popular image used after the plague of 1656 in Naples (PMA). Giordano was heavily influenced by the Neapolitan art of Caravaggio and the work of Jusepe de Ribera (GOA). Though he was also influenced by Pietro da Cortona between 1665-1676, his style varied with the treatment of work (GOA). In his early pictures of saints, Giordano was closely aligned to the style of Ribera, such as the use of a somber palette, observed bodies of men, and patchy illumination (Harris, 139). The work involves a painterly handling of brushwork, defined by the tenebrism, an observed element that appears realistic and references Caravaggio’s influence (Martin, 223). Giordano reflects an interest in penetrating the space and receding background by placing the main action of the figures in the foreground, developing a relationship with the space of the viewer, a visual element emphasized in Spanish religious imagery for devotion. The involvement of the tenebristic light upon the central figures relies upon the senses, continued by the emotive surface with the painterly approach to light (Martin, 54). Giordano presents the body through a dramatic tenebrism, evoking the senses of the viewer and relying upon the dark, monochromatic palette for a naturalistic notion. Giordano involves the Baroque style of dramatic light to create an emotive surface, integrating the senses of the faithful through an atmospheric scene.

Campanelli, Daniela. “Giordano, Luca.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T032371. 21 April, 2013.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art. “Saint Sebastian Cured by Irene.” Collections. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2013. http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/104396.html?mulR= 669|2. 21 April, 2013.

Late Baroque Illusionism

Giovanni Battista Gaulli (Il Baciccio), Triumph in the Name of Jesus, 1676-1679, nave fresco, Late Baroque, patron: Gian Paolo Oliva, Father-General of the Jesuit Order, fresco, Il Gesù, Rome

Giovanni Battista Gaulli’s (1639-1709) The Glorification of the Holy Name of Jesus represents the Late Baroque style of various blends of medium in the pursuit of a dramatic representation. Gaulli was commissioned in 1672 by Gian Paolo Oliva, Father-General of the Jesuit Order, to fresco the domes, pendentives, and the nave and transept vaults of Il Gesù, supported by Bernini (GOA). The paintings of the pendentives represent the metaphysical transition between vision of heaven in dome and the congregation of the church (GOA). Gaulli involves drama, movement, and saturated colors, leading to various rhythms over the surfaces (GOA). The vault of the nave represents the hosts of heaven kneeling in adoration before divine light, which illuminates from a monogram of Jesus (GOA). The blessed ascend to heaven and the damned to hell, dividing the composition into divisions with the arc of clouds spreading beyond the frame (GOA). The central zone involves a group of cherubs, rising around a mystical light source and sharply foreshortened (GOA). Gaulli involves the details of the effects of light, as the cherubs closest to earth have solid forms, while the light dissolves their mass and lessens the color (GOA). The section of the blessed figures has the illusion of being on a level just below the vault of the church, as the clouds continue over the architectural decoration (GOA). Gaulli’s figures are reminiscent of Bernini’s mature figure style with the elongated forms and curly hair since Bernini helped him design some areas (Harris, 132). The human form emphasis leads to an illusion of a tangible existence with the blessed figures (GOA). Gaulli involves the light in the pursuit of the dramatic work, as the damned continue over the frame, driven downward by light (GOA). The appearance of the nave open to the sky, as figures float up into heaven or fall to hell is continued with the illusion of reality, as many figures are in extreme foreshortening (Harris, 133). The use of illusion, with light, drama, and movement, blurs the heavenly and earthly spheres to respond to the viewer (GOA). At the summit of Gaulli’s fresco is a loop of ribbon, inscribed with the words from a verse in the Epistle of St. Paul, referencing the Church spreading faith throughout the world, a Jesuit focus and ultimate theme of the nave (Harris, 133). The richly decorated architecture framework with the gilded plaster relates to Gaulli’s blend of painting, sculpture, and architecture, a Baroque theme (Harris, 133). Gaulli’s fresco utilizes dramatic representation in religious pursuit to affect the viewer.

Enggass. “Gaulli, Giovanni Battista.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T031034. 30 April, 2013.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.