Bernini

Gianlorenzo Bernini, Towers for façade portico, 1637-1641, destroyed in 1646, High Baroque, patron: Urban VIII, St. Peter’s, Rome

Bernini’s towers for the façade portico reflect his reliance upon papal patronage and the shift in his career. In 1629, Bernini was appointed architect to the fabric of St. Peter’s (GOA). By 1636, Bernini was designing a remodeled version of two bell towers begun by Maderno, and flanking the façade of the basilica of St. Peter’s (GOA). Bernini’s design of the bell towers’ for the façade rested on underground springs, unstable foundation (Hibbard, 118). The south tower was completed and cracks resulted in the structure (Hibbard, 118). The bell towers were demolished under the papacy of Innocent X and secured the end of Bernini’s position as papal favorite. The destruction, representing Bernini’s shift away from reliance on the papacy to other commissions, also resulted in commissions for other artists in Rome.

Hibbard, Howard. Bernini. New York: Penguin Books. 1965.

Mezzatesta, Michael P., and Rudolf Preimesberger. “Bernini.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T008287pg2. 2 April, 2013.

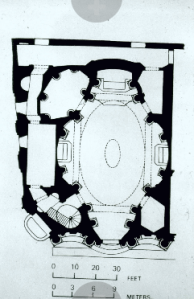

Gianlorenzo Bernini, S. Andrea al Querinale, 1658-1670, High Baroque, patron: Jesuits, funded by Prince Camillo Pamphili, Rome

Bernini’s S. Andrea al Querinale represents the High Baroque architectural style of concave and convex elements to engage the viewer. With the layout of Rome, artists designed façades to entice the viewer into the church, serving as a centralizing form that would dynamically embrace the viewer. Orders were made to have a sculptural plasticity, while the façade reflects the crowded urban environment and Bernini’s awareness of the contemporary architectural work in Rome. The recessed arms and entrance responds to a tight urban environment. The use of recession and undulating forms become a pattern for High Baroque architecture, with the alternating concave and convex curves. The long narrow site led to Bernini utilizing an oval plan, but giving the movement of a longitudinal plan, also using the symbolic qualities of a centralized plan. By placing the axis on the long side, Bernini brings a direct focus on the altar as the viewer enters the building. The façade includes the idea of concave and convex alternating rhythms, while also classical and stable forms. The classical temple portico creates a two-story reading of the façade, the monumental triumphal arch form and the entablature at another level, which matches the interior. The exterior towards the street with the steps echoes the shape of the convex portico. Bernini adopts a more dynamic alternation of shapes and return to classical forms, such as with the circular temple. The interior is dedicated to St. Andrew, as Bernini merges decoration and iconography together. He treats the architectural space similar to his treatment of sculpture, relying upon a concetto and bel composto, as the spectator perceives the whole, then walks around to experience the many views. The high altar represents the martyrdom of St. Andrew, with the statue of the saint rising into the heavens, and above the statue, the dome. Bernini creates a three-dimensional spatial container for a sculpted and painted program, symbolically representing the martyrdom and ascension through architecture and light coming through the windows of the high drum. Bernini involves art and nature through his use of natural light and depicted light to create a religious experience for his viewer.

Gianlorenzo Bernini, Scala Regia, 1663-1666, High Baroque, patron: Alexander VII, Vatican, Rome

Bernini’s Scala Regia represents his mastery of space and illusion. The stairs were ceremonial for the pope, leading to the Vatican Palace from St. Peter’s. The remodeled stairs required a suitable design for the elderly pope and a lighted passage (Hibbard, 163). The stairs went up different levels to the main floor of the Vatican Palace. From the viewpoint of looking down the portico of St. Peter’s, Bernini created the appearance of a regular space going up. Where the stairs were narrowest, Bernini made the passage look wider with the use of columns (Hibbard, 163). The below view, with more width available, Bernini set the columns out from the wall, while the higher view, as the passage goes in, columns were placed closer to the wall and diminished in height (Hibbard, 163). As the viewer stands below, the narrowing above appears to be a standard height and width through Bernini’s use of illusion (Hibbard, 163). Bernini utilizes sculpture and windows for the landing when breaking the space, while employing natural light (Hibbard, 163). Bernini manipulates classical regularity and perspective to achieve a monumental space and illusion, characteristic of the High Baroque.

Hibbard, Howard. Bernini. New York: Penguin Books. 1965.

Borromini

Carlo Maderno, Gianlorenzo Bernini, Francesco Borromini, Palazzo Barberini, 1628-1633, High Baroque, patron: Barberini family, Rome

The Palazzo Barberini illustrates the High Baroque styles of shifting toward a new palace plan, while including the collaboration of several architects. The Palazzo Barberini represented the fusion between palace and villa. The cardinal nephews of Urban VIII were responsible for increasizing the size of the palace, which includes a typical urban façade with an open lower arcade, as the courtyard also displays the function of a villa with the fountain and open wings. The work was first designed by Carlo Maderno (1555-1629) for the Barberini family, before Urban VIII became pope, eventually becoming papal architect while designing the villa, including the work of Gianlorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini (1599-1667). Borromini moved to Rome in 1619, able to work with his distant relative Maderno on the Palazzo and eventually the façade and nave of St. Peter’s (GOA). The architecture of the Baroque period signified an expansion in scale, as seen with the Palazzo Barberini and the merging of types, referencing Renaissance models, such as the Villa Farnesina. The Palazzo continues the High Baroque dynamic quality, as seen with the fenestration. The window treatment integrates the use of classical orders on the façade, using superimposition. The treatment transitions from the lower story, upwards, moving to an increase in orders, leading to an expressive purpose of the orders, while offering a structural support in the transitional elements. Maderno centralized the focus, emphasizing the central bay with the parapet, an area used for ceremonial purposes. Typical of a Baroque façade, there is a reliance upon a central axis and a movement toward the center with the dynamism of recessing architectural elements. After Maderno died, Bernini took over the project, a favorite of the Barberini family, as Borromini stayed on. Borromini became responsible for the top story and fenestration, integrating a more perspectival frame. Bernini was possibly accountable for the main piano mobile story, continuing Maderno’s plans. Borromini’s handling of the square windows, on either side of the double arcade windows, was adapted from the square attic windows of Michelangelo at St. Peter’s (Harris, 80). Borromini however integrates the dynamic and dramatic quality of the High Baroque by having the pediment angled forward at the sides, before curving over a scallop shell in the center, as stylized garland hangs over (Harris, 80). Borromini’s side window treatment took on sculptural quality in the treatment of the frame. The upper story window frame and addition of the parapet also defined the High Baroque dynamism and lively appearance, as Borromini put the entablature of the window frame on an orthogonal treatment. With this treatment, the arch appears to have depth with the perspectival approach. The H-shaped plan of the building mixed the urban and villa shapes, utilizing the wings as a mixed form. The new plan also illustrated an illusion coextensive space, with the open courtyard and flow of space (Martin, 188). The H-plan allowed the opportunity to develop a new type of interior, with new traffic patterns, such as a hallway inside. The interior of the Palazzo involved a monumental staircase to enter the upper story, becoming part of the development of ceremonial staircases, later oval staircases by Borromini. The arrangement of the interior spaces involved apartments, a cluster of rooms associated with a single individual. Borromini’s collaboration on the Palazzo ended in 1631 after a fight with the Barberini family regarding the project (GOA). The Palazzo represented Borromini’s early developing characteristic of utilizing the curve for architectural surfaces to signal the High Baroque.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

Martin, John Rupert. Baroque. New York: Harper & Row. 1977.

Stein, Peter. “Borromini, Francesco.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T010190. 17 April, 2013.

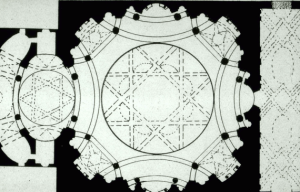

Francesco Borromini, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (“San Carlino”): cloister, church plan and interior; façade, 1638-1667, High Baroque, patrons: Spanish Discalced Trinitarians, Rome

Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane illustrates the High Baroque focus upon space and curvilinear movements. In 1634, Cardinal Francesco Barberini helped Borromini gain his first commission as an independent architect, with the monastery and church of S. Carlo for the Spanish Discalced Trinitarians (GOA). The monastic building was finished by 1636, but the work on the church did not begin until 1638, culminating in the façade finished in 1677. Borromini had to fit multiple elements of the church and monastery in a small area, adjusting to the urban environment. The monastic building with a small courtyard included a convex curvature of its corners and pairs of monumental Doric columns (GOA). Pairs of columns were at the angles, next to the convex protrusions of the walls that supported an arched opening at each end (Harris, 81). Borromini used smaller columns to support the upper walkway that included a balustrade with vase-shaped balusters alternately inverted, thus emphasizing a rhythm and movement, an element of High Baroque architecture (Harris, 81). The oval plan involved a symmetrical, quatrefoil design, including the oval form of the dome and half-oval curves of the side chapels (GOA). The sections of semicircles forms are alternated with flat surfaces (GOA). Half ovals were at each end of the cross axis, and semicircular sections at either end of the longitudinal axis, ultimately two convex intrusions (GOA). The entrance and altar face each other on the long axis (Harris, 81). The alternating forms emphasized movement and a dynamic interior, characteristic of the High Baroque use of space. The interior, specifically the lowest level to the main entablature, involved alternating curved and straight areas of the wall, along with arches (GOA). Above the entablature, there were the dome pendentives, along with the half-domes of chapels and their arches (GOA). The pendentives were created by four semi-domes that supported the main oval dome, as the pendentives depicted the life of St. Charles Borromeo (Harris, 81). For the upper story of the interior, Borromini created an illusion of the dome being suspended with the use of a dome ring to hide the base of the coffered oval bowl (GOA). Borromini created an illusion of height through the interlocking forms (Harris, 81). Borromini also created a unity in the interior with the use of columns, either framing or acting as support for arches (GOA). The movement of walls and “sculptural volumes by the columns” become the main elements of the interior (GOA). The use of movement and alternating forms continued to the façade. The upper level was completed by Borromini’s nephew, including three concave bays instead of Borromini’s use of alternating concave and convex (GOA). The lower part of the façade was completed by the time of Borromini’s death. The façade includes the alternating concave-convex-concave form, while using large columns with small ones on both levels (Harris, 82). Borromini utilizes the space and the power of the curve to create movement. The façade involves an advance in the center, an illusion of a forward thrust (Martin, 190). Borromini’s design reflects the complex use of space in the High Baroque architecture, while using the surface to emphasize movement.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

Martin, John Rupert. Baroque. New York: Harper & Row. 1977.

Stein, Peter. “Borromini, Francesco.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T010190. 17 April, 2013.

Francesco Borromini, Oratorio of the Filippini: monastery; oratory and façade, 1642-1650, High Baroque, patrons: Oratorians, Rome

Borromini’s Oratorio of the Filippini continues the High Baroque concave projections and the use of illusion of space. The Oratorians appointed Borromini as chief architect for their community building in 1637, adjacent to the Chiesa Nuova (GOA). He was assigned to execute the design of the previous architect, Paolo Maruscelli, though Borromini left in 1652 due to difficult relations with the Fathers in completing work (GOA). An attractive exterior was desired, though the Fathers did not want to compete with the Chiesa Nuova, leading to Borromini making the façade lower and with a cheaper material (GOA). Borromini was able to display his skill though in using the brick for decorative effects (GOA). The plan for the oratory was for a rectangular interior, meant for the Order’s sermons and choral music (Harris, 84). The building also included motifs connecting to palazzi, such as the main staircase modeled on the Palazzo Farnese (GOA). A concave plan was across the five main bays, emphasized by the pediment with curves and straight lines (Harris, 84). Borromini continued the use of curves and movement to create a dynamic façade, such as the central bay on the ground floor is convex, while the bay above is concave (Harris, 84). Borromini uses the inverted baluster for the balustrade above the main cornice, creating the rhythm as seen with his previous designs (Harris, 84). Similar to his other works, Borromini provided adaptations to traditional styles. Roman façades were previously straight, however, Borromini replaced the objectivity with a new subjective approach that was underlined by the emotion of concave and convex rhythms (GOA). He also creates an illusion that the building extends further, but the hall is across the façade and extends at the sides (GOA). Borromini utilizes High Baroque elements of emotion in the format of architectural design and movement.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

Stein, Peter. “Borromini, Francesco.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T010190. 17 April, 2013.

Francesco Borromini, Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza: courtyard; church exterior with dome and lantern; plan and interior, 1642-1650, High Baroque, Rome

Borromini’s Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza relies upon the dynamic quality of the exterior and lantern. Giacomo della Porta had already designed a round church, but Borromini created a centralized, domed church (GOA). The ground plan includes triangles with apexes cut away in a concave curve (GOA). The centers of the sides thrust forward to create large semicircles (GOA). Both levels of the arcades of the cloister goes across the concave façade (Harris, 82). Borromini continues to utilize undulating forms to suggest movement in the space, thus involving the viewer. The next level also includes a low concave wall, with oval openings filled with an eight-pointed star, a screen for the lower area of the drum of the dome (Harris, 82-83). Borromini involves the Chigi coat of arms, integrated with the dome like turrets, since the church was completed during the papacy of Alexander VII (Harris, 83). The movement of design continues with the lantern, a spiral shape, possibly referencing the path to wisdom (GOA). The interior design alternates concave and convex sections, becoming concave at the lantern level (Harris, 83). The plan of the domed church is in a six-pointed star, representing the dedication of the church to wisdom, sapienza (Harris, 83). The interior was lit only form the dome, but manipulated to illuminate the altar area (GOA). Borromini involves alternating forms and light to create a dramatic interior space.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

Stein, Peter. “Borromini, Francesco.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T010190. 17 April, 2013.

Francesco Borromini, Sant’Agnese in Agone: façade (Palazzo Pamphili and church begun by Girolamo Rainaldi and son Carlo), 1652-1668, High Baroque, patron: Innocent X, Piazza Navona

Borromini’s Sant’Agnese in Agone involves the focus upon space when integrating the architecture in a larger environment. Borromini was commissioned by Innocent X in his plans for the Piazza Navona, integrating his extension of the Palazzo Pamphili (GOA). With the new façade, Innocent X wanted to unite the parts of the building (GOA). Borromini’s design for the Palazzo was rejected, and Girolamo Rainaldi and his son Carlo took on the project due to the conservative taste of the pope (GOA). In 1646, Borromini added a large gallery to the palazzo, which opens onto the Piazza Navona (GOA). In 1653, the pope dismissed Rainaldi and his son as supervising architects for S. Agnese, as Borromini was hired (GOA). Borromini was meant to involve the small early Christian church and also to house the tomb of the pope, while serving as a chapel of the neighboring family palazzo (GOA). Borromini demolished the façade, but emphasized his characteristic curved form, making space for stairs in front of the church, in order to not break into the piazza (GOA). Borromini wanted to continue his Baroque sense of movement with the proposal for the crossing piers. The proposal included making them convex and go into the crossing area, but requiring a different kind of dome (GOA). The pope rejected the idea with is conservative taste, retaining the dome with a drum (GOA). The façade involved concave link blocks that connected with two west towers, creating a rhythm of the forms and extending the façade sideways into the area of the palazzo (GOA). Ultimately, Borromini established a concavity of the façade, with the convex thrust of the dome and the concave blocks (GOA). Borromini was dismissed in 1657 by Prince Camillo Pamphili (GOA). Borromini continues the recessive movement in the façade design, while creating a monumental space linked to the pope’s family.

Stein, Peter. “Borromini, Francesco.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T010190. 17 April, 2013.