Seville

Juan Sánchez Cotán, Still Life with Quince, Cabbage, Melon, and Cucumber, c. 1602-1603, Spanish High Baroque, oil on canvas, 27″ x 34,” San Diego, CA

Juan Sánchez Cotán’s (1560-1627) Still Life with Quince, Cabbage, Melon, and Cucumber represents the emerging naturalism of the Spanish High Baroque. Cotán was prominent for his still lifes, working in Toledo that included patronage among intellectual circles for secular objects (GOA). Naturalism began to become prevalent in seventeenth-century Toledo, as evident with the private collections holding paintings of fruits and vegetables by Cotán (Tomlinson, 56). These paintings were identified according to the contents, illustrating Cotán’s focus on individual objects (Tomlinson, 57). With many of his still lifes, Cotán arranges the objects in a shallow niche, a window ledge that references the architectural features of Spanish houses during the period (GOA). The background is characteristically a dark space, as the window becomes a form of stage as art imitates nature (GOA). Cotán plays with light and shadows upon the fruit, such as the melon pieces, and the heavy shadows of the window ledge, therefore defining the space (GOA). His closely observed forms continue the illusion of reality (GOA). The fruits and vegetables in the work are organized according to a mathematical curve (GOA). The “austerity” that characterizes his still lifes is possibly a “transfiguration of the commonplace,” reflecting a spiritual focus upon the object, similar to the contemplation promoted in the Spiritual Exercises by St. Ignatius Loyola (Tomlinson, 58). Cotán focuses upon the naturalism in the observation of forms in the pursuit of an illusion of reality.

Jordan, William B. “Sánchez Cotán, Juan.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T075605. 23 April, 2013.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

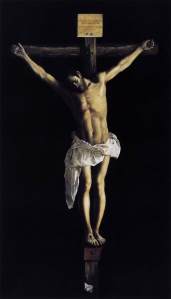

Francisco de Zurbarán, Christ on the Cross, 1627, Spanish High Baroque, patron: Seville monastery of San Pablo el Real, oil on canvas, 9′ 6 3/4″ x 5′ 5,” Art Institute of Chicago

Francisco de Zurbarán’s (1598-1664) Christ on the Cross reflects the naturalistic tendencies of Spanish painting and the importance of mystical communion. In Spain, Counter-Reformation ideals continued with the purpose of religious images teaching or serving as a communion tool for the viewer (Tomlinson, 62). After studying in Seville, Zurbarán’s work is characterized by heavy folds of drapery and attention to detail, following naturalism (GOA). The work was commissioned by the Seville monastery of San Pablo el Real, in which the image would have been seen entering the church before celebrating Mass, as the image reinforces the religious service performed in the church (Harris, 217). Zurbarán includes no narrative details, such as a lack of setting, but focuses upon the body (Tomlinson, 69). The precise handling and use of chiaroscuro gives volume to the emaciated form highlights the drapery (Tomlinson, 70). The precise handling and chiaroscuro creates an illusion of reality for the work to become a tool in mystical communion. The body emphasis is meant to inspire meditation on Christ’s humanity and sacrifice (Tomlinson, 70). Zurbarán relates to the Spanish art theorist, Francisco Pacheco stating the intent of religious images, “perfect our understanding, move our will, refresh our memory of divine things” (Tomlinson, 70). Spanish painting during the High Baroque focuses upon achieving a realism for the viewer to bring them closer to a mystical communion with the divine (Martin, 55). The realism of the figures also reflects the awareness of Caravaggio’s aesthetics of strong lighting (GOA). The verisimilitude is achieved by the trompe l’oeil paper pinned to the bottom of the canvas, serving as a calling card of the artist and reflecting his skill (Tomlinson, 70). The work was part of a set of commissions for twenty-one paintings from the Dominicans of San Pablo (Harris, 217). Zurbarán’s popularity rose after this work, leading to an invitation in 1629 to move to Seville permanently (GOA). Zurbarán exhibits his characteristic tendency toward realism to achieve an illusion, ultimately to create a reflection upon the divine.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

Jordan, William B., and Claudie Ressort. “Zurbarán, de.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T093699pg1. 23 April, 2013.

Martin, John Rupert. Baroque. New York: Harper & Row. 1977.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

Francisco de Zurbarán, The Annunciation, 1650, Spanish High Baroque, patron: Gaspar de Bracamonte, for sacristy of San Miguel in Penarande de Bracamonte, oil on canvas, 85 5/8″ x 124 1/2,” Philadelphia Museum of Art

Zurbarán’s The Annunciation illustrates the Baroque interest in illusionism, specifically in relation to a religious scene. Spanish painting during the Baroque became characterized by religious scenes treated in a straightforward manner to manipulate the viewer in prayer. Zurbarán takes on the scene in an intimate setting, while originally for a larger audience. He depicts the idea of the supernatural, with the vision made manifest. Zurbarán is often associated with Caravaggio and emotional intensity, however the scene is represented in a calm manner. The piece of paper is a characteristic of Zurbarán’s work, a way of showing his skill and his interest in illusionism, continued with the vase and play of light. He responds to the Carracci naturalism by retaining the calm treatment and illusionism, instead of the heightened drama of Caravaggio. With the point of view, Zurbarán creates a platform, wit the perspective of looking down, a Northern treatment, since many Spanish artists were looking at art coming from other parts of Europe. The curtain reveals the scene, creating an idea of a real scene with the stage-like setting. With the stage-like scene, Zurbarán maintains an intimacy and emotional resonance with the atmospheric effects, continuing a meditative work for the faithful viewer.

Jordan, William B., and Claudie Ressort. “Zurbarán, de.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T093699pg1. 23 April, 2013.

Diego Velázquez, Christ in the House of Mary and Martha, 1618, Spanish High Baroque, oil on canvas, 23 3/4″ x 41,” National Gallery, London

Diego Velázquez’s (1599-1660) Christ in the House of Mary and Martha demonstrates his early career of naturalism that aligned with the Spanish Baroque trend in naturalism for religious meaning. Velázquez studied with Francisco Pacheco, beginning in 1611, leading to his knowledge of Christian iconography (GOA). Velázquez began to also learn the tenebrist naturalism of Caravaggio, seen in his bodegones, or genre paintings that included still lifes (GOA). The two figures and still life share the foreground, ultimately representing the importance of representing the closely observed natural world (Tomlinson, 67). The background scene consists from a scene from the Gospel of Luke, describing Christ’s visit to the house of Martha and Mary (Tomlinson, 67). The religious scene represents Mary listening to Christ, but admonished by Martha for ignoring her work, though Christ says she is following the righteous path (Tomlinson, 68). The idea of Martha and Mary resonate with the foreground figures of the old woman and kitchen maid. The bodegones take on a moral message with Velázquez, reflecting the religious focus in Spain. The kitchen maid is possibly indignant at having to prepare a meal, as the old woman reminds her of Christ’s rebuke to Martha (Martin, 133). Velázquez paints a “scene within a scene,” a compositional type repeated in his work and possibly inspired by Northern compositions, such as by the Flemish painter, Pieter Aertsen, to enrich the meaning of the painting (Tomlinson, 68). The imagery of the servant is also seen in Velázquez’s teacher’s treatise, El arte de la pintura (1649) by Pacheco, in which he stated the “aim of painting is the service of God,” reflecting the religious significance of genre paintings (Martin, 133). The peasant pictures of Velázquez take on a religious tone, transcending the earthly naturalism and reality (Martin, 134). He also uses a tenebrist tone for the scene, as it remains vague whether the religious scene is a real event occurring, painting on the wall, or mirror reflection (GOA). Velázquez continues naturalistic tendencies for the pursuit of a religious significance.

Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. “Velázquez, Diego.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T088463. 23 April, 2013.

Martin, John Rupert. Baroque. New York: Harper & Row. 1977.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

Madrid

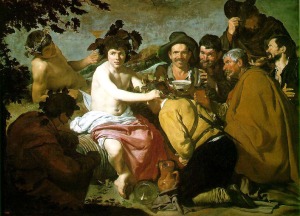

Diego Velázquez, Feast of Bacchus, c. 1628, Spanish High Baroque, oil on canvas, patron: during stay at royal court of Philip IV, 65″ x 88 1/2,” Prado, Madrid

Velázquez’s Feast of Bacchus represents his continuation of naturalism in the progression of his career. In 1623, Velázquez goes to Madrid, reaching success after his royal portrait of King Philip IV, and later studying in Italy to become acquainted with Venetian painting, as his palette lightens in Madrid (GOA). The work reflects the contemporary interpretation to a mythological subject matter, similar to the religious images of Caravaggio (GOA). The scene illustrates a visit to mortals by the god Bacchus, giving the gift of wine (Tomlinson, 90). Bacchus places a wreath on a soldier, while poor peasants surround him, reflecting the gift of wine as a deliverance from misery (Martin, 50-51). Velázquez depicts the peasants as realistic types, as seen with his earlier bodegones (Tomlinson, 90). There is a difference with the flesh of the god and mortals, though Bacchus is still depicted realistically (Tomlinson, 90). The realism of the peasants, a Sevillian style of the work, continues the naturalism of the Baroque by utilizing real people as models (Harris, 229). His biographer Palomino described Velázquez’s work in 1724 as “not painting, but truth” (Martin, 50). He becomes characterized by his use of luminous contrasts and dense coloring, as well as the integration of still-life details, marking the foreground space (GOA). Velázquez supports the naturalistic tendencies by the use of harsh realism to reinterpret a mythological scene.

Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. “Velázquez, Diego.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T088463. 23 April, 2013.

Martin, John Rupert. Baroque. New York: Harper & Row. 1977.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4e/Velázquez_-_de_Breda_o_Las_Lanzas_(Museo_del_Prado,_1634-35).jpg/350px-Velázquez_-_de_Breda_o_Las_Lanzas_(Museo_del_Prado,_1634-35).jpg

Diego Velázquez, The Surrender at Breda, 1634-1635, Spanish High Baroque, patron: Philip IV, oil on canvas, 10′ 1″ x 12,’ Museo del Prado, Madrid

Velázquez’s The Surrender at Breda reflects his looser style while evoking the importance of space and painting for the Baroque period. From 1633-1635, Velázquez and other artists were commissioned to paint twelve large pictures depicting Spanish military triumphs for the Hall of Reams (Harris, 230). The Hall of Reams was in the Palacio del Buen Retiro, built for the king at the behest of Conde de Olivares (GOA). The work illustrated an historical event, for the purpose of Spanish propaganda in a room for court ceremonies and royal audiences. The battle scene illustrates the surrender of the Dutch general Justin of Nassau to Ambrogio Spinola, general of the Spanish forces, in Breda (Tomlinson, 92-93). Velázquez completes a classically balanced composition, with the group of Spanish victors on one side and defeated Dutchmen on the left, also reflecting the surrender as a symbolized key is given to Spinola (GOA). The lances on the Spanish side also represent the Spanish victory (Tomlinson, 94). Velázquez achieves a luminosity with the use of white underpainting, while using a technique of strokes of color, borrones, to define the form, a technique compared to Titian (Tomlinson, 93, 97). He includes naturalism with the attention to light upon the various forms (GOA). Velázquez unifies the foreground action and background, including the horse on the right to lead the viewer to the soldiers in the rear, ultimately a visual progression (Tomlinson, 94). He depicts the Spanish moral superiority, integrating the compositional device of visual distance to refer to an event being celebrated (Harris, 231). Velázquez illustrates the development of his style, departing from precise handling, while representing a scene that supports the image of his patronage source, the royal court.

Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. “Velázquez, Diego.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T088463. 23 April, 2013.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, c. 1656, Spanish High Baroque, oil on canvas, 10′ 5 1/4″ x 9′ 1/2,” Museo del Prado, Madrid

Velázquez’s Las Meninas demonstrates the importance of space in the Baroque, and the nobility of painting. In the early 1640s and his later career, Velázquez’s produced less work due to his responsibility as a member of the royal household (Tomlinson, 98-99). Velázquez considers the theme of the nobility of painting with the play of perspective and space. He depicts the royal household while including a self-portrait of himself working behind the canvas (Harris, 237). Infanta Margarita and her attendants are represented, along with the portraits of Philip IV and Mariana in the reflections of the mirror (Harris, 237). The work demonstrates the immediate truth of what is seen, such as the royal household, while Velázquez is in the act of painting, facing out toward the viewer (GOA). The viewer takes on that of the artist’s subject (GOA). However, the mirror reflects images of the king and queen, as the royal couple is the models, which Velázquez paints and are the viewers of the painting (GOA). The members of the household appear to be looking out at the royal couple posing for their double portrait (Harris, 237, 239). The orthogonal, perspectival lines meet in a vanishing point beneath the arm of the man in the doorway, as the ideal viewer would be before this point, but the viewer stands to the right of the king and queen in the mirror (Tomlinson, 105). The work plays with the perspective, considering if it is actually the king and queen in the space or the painting reflection, as the viewer becomes the bystander of the painter in the presence of the royal patrons (Tomlinson, 105). Velázquez involves three-dimensional space, dealing with presences within and outside the painting, while creating psychological and spatial tension between work of art and beholder (Martin, 168). Velázquez also portrays himself as an intimate member of the royal family, furthering his claims for the nobility of painting and a higher social standing for himself (Harris, 239). He wears the red cross of the order of the Santiago, added after he was granted the title in 1658 (GOA). Velázquez achieves the royal admiration, utilizing this element to further the noble status of painting and separate from manual labor, but intellectual with the perspectival play (Tomlinson, 104-105). Velázquez considers the Baroque focus upon space and the inclusion of the viewer, while continuing his aims to elevate the status of painting.

Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. “Velázquez, Diego.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T088463. 23 April, 2013.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art & Architecture, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. 2008.

Martin, John Rupert. Baroque. New York: Harper & Row. 1977.

Tomlinson, Janis. Painting in Spain, El Greco to Goya: 1561-1828. London: Calmann & King Ltd. 1997.

Seville

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Christ Bearing the Cross, c. 1665-1675, Spanish High Baroque, oil on canvas, 60 3/4″ x 83,” Philadelphia Museum of Art

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo’s (1618-1682) Christ Bearing the Cross represents the naturalistic approach to religious scenes by Baroque artists. Murillo was trained in Seville and was associated with a softer, atmospheric quality with lighter palette, though later in his career, shifting to brown and gray shades (GOA). The work takes on a meditative tone, furthered by the darker palette and Christ’s increased contact with the viewer with the eyes, leading to more intimacy between viewer and figures. Murillo focuses light on the faces and hands, the most expressive aspects of the composition, while also helping the eye to lead around the canvas. The soft light of Murillo is included, creating an emotional resonance and meditative function, since there are less figures in the religious scene. The dress of Christ is a monastic references, possibly reflecting the patronage source. The work becomes iconic rather than narrative, though Murillo retains naturalism with the dark palette and observation of detail, such as the Caravaggio setting and naturalism of the figures, along with the use of tenebrism for a dramatic scene to inspire the viewer in prayer. He retains an emotive scene, especially with the soft strokes compared to Caravaggio’s precise work, furthering the intimacy of the religious scene for a Spanish viewer.

Mena Marqués, Manuela B. “Murillo, Bartolomé Esteban.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordartonline.com.libproxy.temple.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T060472. 23 April, 2013.